The Eiger, Bernese

Oberland, Switzerland, 24 July – 3 Aug 2005

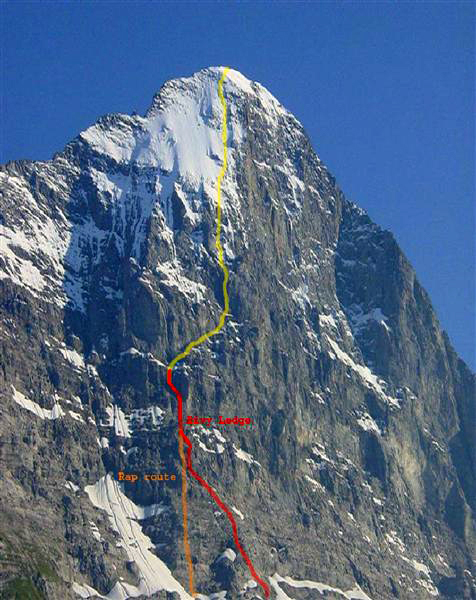

Eiger – Round One.

North Pillar (Nordpfeiler), Austrian Route, Difficulty: TD, V.

First Ascent: 30 July-1 Aug 1968 Tony Hiebeler, Reinhold and Gunter Messner,

Frank Maschka

We started the approach by taking the cog train from Grund to Apiglen. After a two hour quad-burning, oxygen-sucking approach from the train station through cow pastures we started climbing at 8:30 a.m.

Eiger translates to ogre in English…an appropriate name. After reading a London Telegraph article warning of the serious rock fall on the Eiger due to global warming we decided to attempt the North Pillar due to it being on a buttress and reportedly relatively safe from non-self-induced rock fall. The Eiger has been described as a giant pile of choss. It is. Cannon cliff is no comparison for loose rock. It is composed of crumbly limestone that breaks into razor sharp shards. I pulled down so many rocks that I quit yelling “rock” unless I thought it was in Peter’s direction. Everywhere we grabbed or put our feet was suspect. I sent one block whizzing by Peter’s head that was the size of a beach ball.

After 10 hours of climbing we were 13 pitches up. Most of the climbing was not technically difficult but it required complete concentration as it was all loose with almost no protection. All day long a Swiss Air-Rescue helicopter periodically flew by; an ominous sign. I had just finished leading a dripping wet pitch with worthless protection on snot-slick rock complicated by mountain boots and a 20-lb pack when we decided we had to bivy. Everywhere there was water. Waterfalls cascaded down the route from the melting snow fields above. We couldn’t find a flat, or even a semi-flat, ledge to bivy on and nothing dry. The only thing we did find was a pair of rusty circa 1960s? strap-on crampons. From the first ascent party? It was now 9:00 p.m. and we decided to rappel down to the last place where we remembered a possible bivy. Three pitches down we found a ledge that was a small promontory on a flat rock. It was exposed to rock fall and lightning but the sky was clear, the rock should be freezing up eliminating rock fall, and at that point we didn’t really care. We had to rest. Peter pounded in a couple of knifeblade pitons we anchored everything and crawled into our bivy bags. The view of the stars and the lights of Grindelwald 7,000 feet below were beautiful and we could hear the constant clanging of the cow bells from the cow pastures far below but the ambiance was anything but idyllic. Sleep was impossible. We lay there shivering in freezing temperatures, the rock sucking the warmth out of us, the wind fluttering our bivy bags with every gust. Great fun!

We laughed about

it after we were down

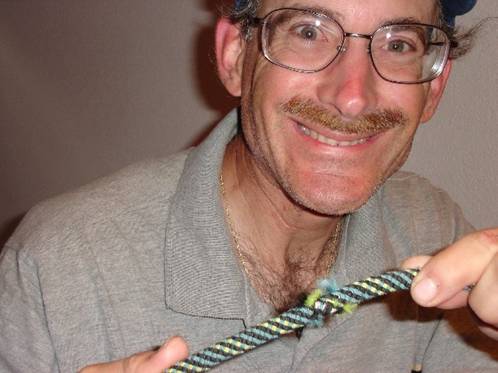

The next morning we looked up and a waterfall was running in full torrent over our route as well as over the Lauper route to our left. I noticed that one of my double nine ropes had an encounter with a rock and the core was showing. Maybe the Ogre didn't want us up there. We decided to head down with the plan to climb the Eiger via the Mittellegi route instead.

We started rappelling at 6:00 a.m. pounding in

pitons and leaving gear as we went down. We did so many raps that I lost count

but managed to leave behind a good portion of my gear including all 15 pitons

that we brought. We rapped down a low intensity waterfall and got our rope

stuck requiring some self-belayed climbing to free it. On our last rap we

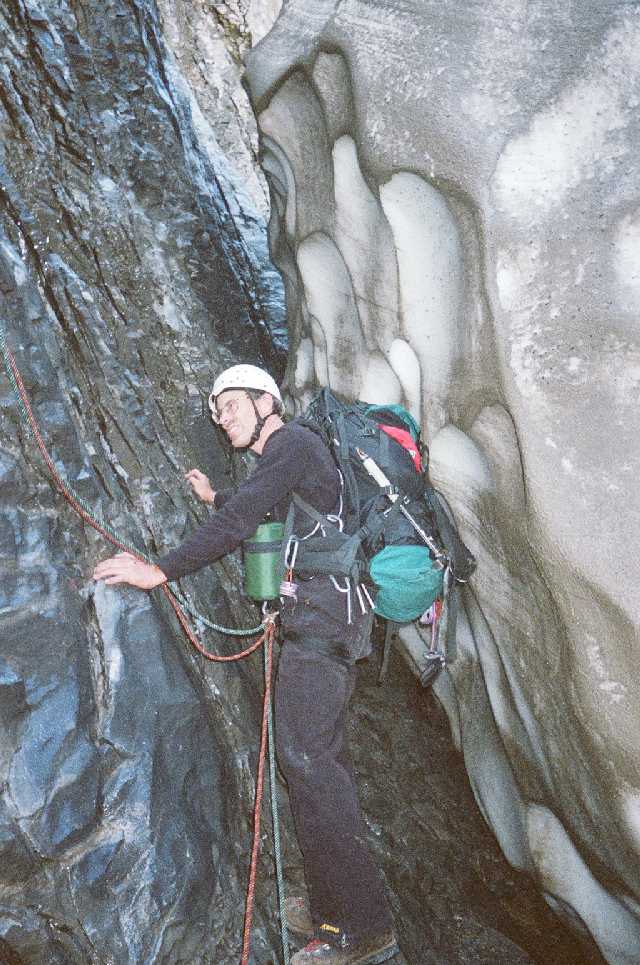

rapped into a bergscrund (crevasse between rock and glacier) and the

claustrophobic refrigerator effect of the ice felt great.

Peter in bergscrund

After maneuvering down the Honysch glacier and a toe screaming descent down the approach trail we were back at the Apiglen train station. We were down! Many of the tourist seeing gear-laden half-crazed climbers fired questions at us in a variety of languages. Yes, we were on the Eiger, we answered. Cameras flashed. We were like rock stars to the paparazzi of tourists.

In retrospect retreat was the only option. We attempted the route at the wrong time of year due to the global warming conditions affecting the Alps. We were aware of the conditions from the London Telegraph article but were hoping that the North Pillar might not be affected. It has to be colder with ice or warmer with dry rock. If we had tried to get through the waterfall or to the upper ice fields the probability of death would have been high. Round One goes to the Eiger.

Eiger – Round Two.

Mittellegi Route, Difficulty: D, IV. First Ascent: 10

Sept 1921 Y. Maki, F. Amatter, S. Brawand, F. Steuri

The approach to this route is the coolest of any route anywhere. You take the Junfraujoch cog train that tunnels through the Eiger. The train stops at two points for the passengers to get out and look out observation windows; once at the North Face and once at the Eismeer Station overlooking the Fieschergletcher (glacier). At the Eismeer Station we got out and opened a small door with the word “Danger” on it in a variety of languages and negotiated an icy tunnel down to another door that opens up to the Fieschergletcher. We then down-climbed to the glacier while a guided party behind us opted to rap. We headed off northeast across the glacier toward the Mittellegehutte (hut). Clouds enveloped us so visibility was poor but we could intermittently see the huge seracs hanging over us to our left. We hadn’t gone more than a hundred yards when we heard a crack and the unmistakable rumble. I yelled “watch out” but really had no idea where the avalanche was coming from or headed to. I only knew it was close. An engine block size chunk of dirty ice followed by a path of snow flew by us across the path we had just followed and between us and the guided party of three behind us. Alpine climbing!

Guide bringing his

clients out of Eismeer tunnel

Trail across glacier to hut

Mittellegi hut perched on ridge

We negotiated the glacier without incident jumping a few crevasses trusting the path of the fresh footsteps in the snow and periodically checking to see if the guide was following. When we reached a rock wall under the Mittellegehutte the guided party caught up to us as we surveyed our options. Not knowing at the time that this was a guided party, I asked if they had done the route before and the guide said no. As he headed up the rock I found out from the clients that he was a Swiss guide from Grindelwald. The common complaint that Swiss guides are jerks held true. We started up the slabs climbing slighly to the right of the party above us to avoid rock fall. It entailed about five pitches of low fifth class rock with concrete rebar for anchors at every pitch.

Peter coming up

toward the Mittellegi hut

The Mittellegi hut is a marvel of Swiss engineering as it

sits precariously perched on a knife edge ridge. We discovered that the day (1

Aug) we were climbing the route was Swiss National Day celebrating the founding

of the country some 700 plus years earlier. The hut was full of climbers and

their guides and we didn't have reservations. Unlike the north side of the

Eiger where we were entirely alone we would have to share this route. The hut

guardian (a pretty young fraulein) grumbled about us not making reservations

down in Grindelwald but managed to find a spot for us to sleep and fed us a

spectacular four course dinner. Another Swiss marvel considering that

everything comes to the hut by helicopter.

Mittellegihutte

We woke before dawn, had a quick breakfast, and started

climbing at 6:30. We were the last party to leave the hut. We roped up short

(20 ft) and headed up a section of third class ridge. Concentration was

critical and the adrenaline was flowing. Even though the terrain is easy here

a trip here would be fatal. Along the entire route you are looking down at

Grindelwald some 5000-7000 ft below on the right and the Fieschergletscher some

3000-5000 ft on the left.

Early morning shot

looking up the Mittellegi Ridge from the hut. The summit is 2013 vertical feet from here.

We came to the first gendarme which is a spike in the ridge that requires climbing. We were careful slow, perhaps too slow, and deliberate but all I could remember was the trip report reporting two climbers who fell to their death through this section. We would have to climb up and down many of these on this saw-tooth ridge and their height ranges from ten to a hundred feet. We would learn that there is a lot more climbing on this route than it appears by looking at the ridgeline. The sun came out in full force and we could see climbers strewn out along the route high above us their helmets like colored pin heads stuck on a map. The first vertical section had a fixed 1 ½” rope which is real handy to clip for protection. There is 200 meters of fixed rope on this route which minimizes the amount of gear you need to bring. The alternative to not clipping the rope is to climb 5.8 crumbly rock with no protection. This is not sport climbing.

This regimen of climbing went on for hours. Every time we

thought the summit was over the next gendarme we encountered another vertical

section. The acclimatization on the North Pillar and a rock

climbing jaunt to the Engelhorner helped our sea-level spoiled lungs with the lack of oxygen. After 6 ½ hours we reached the summit

ridge. It was corniced with snow but we were able to traverse under it on rock

for most of the way. At 12:55 p.m. on 1 August 2005 we stood on the summit of the

Eiger. The only thing marking the spot was an aluminum snow picket someone had

pounded in. We shook hands snapped a couple of hero shots and quickly started

the descent.

Summit hero

shots

Getting off the Eiger is almost as hard as getting up it.

We had two options. One was the West Flank, which has been described as a

steep slate roof with all loose tiles. A British guide in the hut told us to

avoid this descent that no one does it in the summer. There was a recent report of two experienced Spanish climbers who fell to their death coming down the West Flank and the circumstances were never made clear. The other option is the

South Ridge which is also used as an ascent route and rated AD. We

down-climbed, rappelled, climbed over gendarmes on this route for an

interminably long time. The route had icy corniced ridges requiring us to

break out our ice axes and crampons then more rock requiring us to take them

back off. At one spot the ridge ran straight into what appeared to be a dead-end

wall with a ring-pin on it. I had to clip the pin and then reach out blindly

around a corner and grope for a hold then swing around. A fun easy move at the

Gunks but scary in mountainering boots, with a pack, and thousands of feet of exposure.

The ridge went on and on. We watched a Swiss Air Rescue

helicopter flying in and out of the clouds by the summit of the Monch. Someone

was getting rescued. The wind picked up until it howled. At around 4:30 p.m.

it started to snow. We knew we would have to follow the tracks the parties in

front of us left across the Fieschergletscher to avoid the crevasses and

seracs. We stashed the ropes and soloed. The last bit of the ridge ended in

an adrenaline pumping icy corniced ridge of about 55 degrees where we would

punch a hole with our ice axe into the cornice and see the glacier a few

thousand feet below; a final goodbye from the Ogre before we hit the

Fieschergletscher. We were now on relatively flat ground. It was now a snow

slog underneath the entire southeast face of the Monch. We knew there were

giant seracs hanging off the Monch above us as we had seen them earlier when it

was clear. It was better not to see them in what were now white-out

conditions.

Glacier under

southeast face of Monch we traversed in white-out conditions

We could see 20 feet, just enough to follow the foot prints in the snow. After a mile or so of this we negotiated a steep crevassed descent into a large col between the Monch and the Jungfrau. We knew we were close to the Monchjochhutte at this point and after cresting a ridge we could see a small building. It wasn’t big enough for the hut but it had to be close by. When the visibility allowed we saw the Monchjochutte looming above us. We had almost walked by it.

What the Monch Hut looked like in the late evening snow.

We dropped our packs outside and stumbled in the back door at 7:30 p.m. We had been climbing for 13 hours. We found our way to the dining area where they were still serving dinner and ladled down an entire serving bowl of soup intended for a whole table. The next morning after a leisurely breakfast we hiked down the well marked trail to the Jungfraujoch station and caught the train back down to Grund.

Coming down from

Monchjochhutte to Jungfraujoch in white-out

Post Script

I totaled up all the gear I left on the Eiger including the two ropes I donated as clothesline to some friends in Switzerland due to the many rock cuts. Gear lost to the Eiger…$300--Alpine experience…priceless.